Description

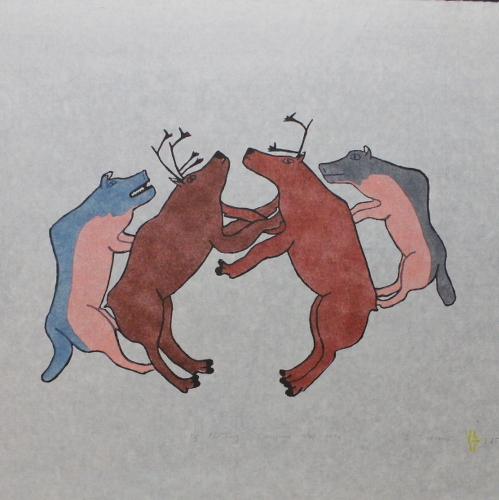

Wolf Hunting Caribou by Simon Tookoome from Baker Lake.

In his youth, Tookoome and other Utkusiksalingmiut lived along the Back River and in Gjoa Haven on King William Island. Here he met and was influenced by the Netsilik Inuit. He moved to Baker Lake, Nunavut, Canada in the 1960s when his Inuit band was threatened with starvation. After the arrival of arts advisors in 1969, Tookoome began to draw and carve stones. He was a founding member of the Sanavik Co-op.

Tookoome died in Baker Lake, Nunavut on 7 November 2010.[4]

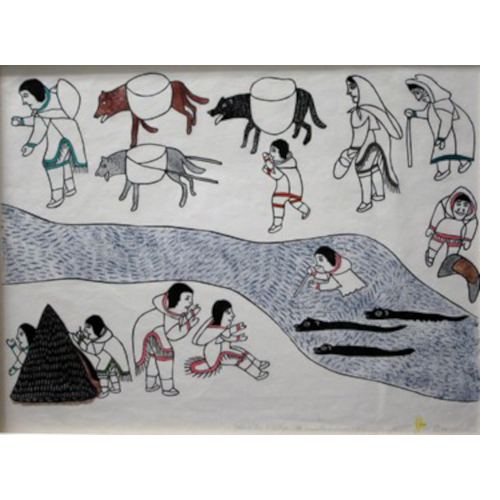

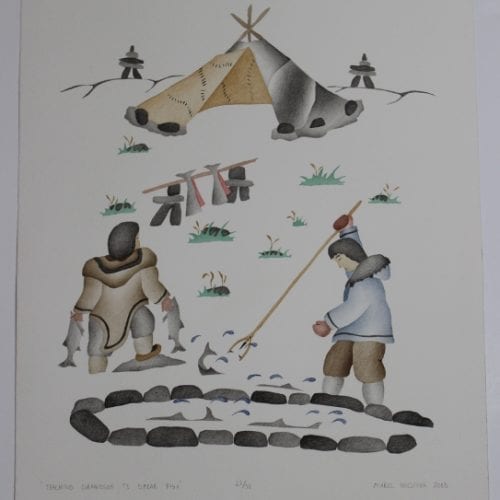

Simon Tookoome was an artist from Tariunnuaq (Chantrey Inlet), NU who lived with his family on the land. At different times in his life Tookoome was a fisherman, a builder, a teacher, a jeweller, an artist and carver with all professions imbued with traditional Inuit knowledge that he always wanted to share, of a traditional way of life

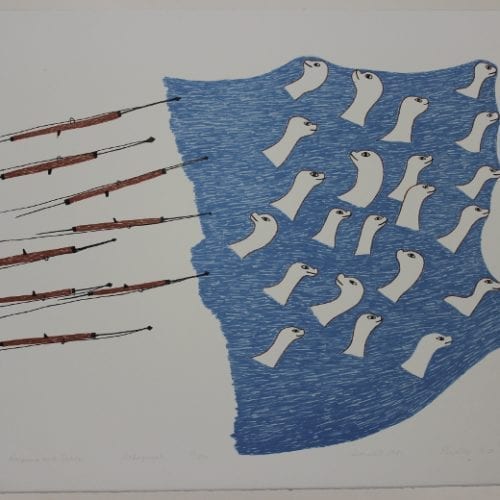

Tookoome began by carving bone and soapstone in the 1960s but was more interested in drawing as it gave him greater artistic freedom Tookoome’s graphic style is influenced greatly by his childhood, being raised on the land and hearing traditional stories from his family. Drawing ideas from the land around him Tookoome’s aesthetic engages with hybrid animals and shamanic practices, influenced by heavy contour lines and deep, saturated tones of colour. Utilizing a flat plane, Tookoome’s drawings have a graphic quality as well as a clear narrative.

Best known for his graphic work, Tookoome has won the Norma Fleck Award for a children’s book titled The Shaman’s Nephew: A Life in the Far North, which he published with Sheldon Oberman in 1999. This autobiographical book deals with Tookoome’s youthful experiences of the traditional Inuit way of life, including experiences with hunting and encountering non-Inuit culture for the first time. He was also included in Irene Avaalaaqiaq Myth and Reality:

In the winter of 1957 to 1958, the caribou took a different route to the calving grounds. We could not find them. All the animals were scarce. We were left waiting and many of the people died of hunger. My family did not suffer as much as others. None of us died. We kept moving and looking. We survived on fish. We had thirty dogs. All but four died but we only had to eat one of them. The rest we left behind. We did not feel it was right to eat them or feed them to the other dogs. My father and his brothers had gone ahead to hunt. We had lost a lot of weight and were very hungry. I left the igloo and I knelt and prayed at a great rock. This was the first time I had ever prayed. Then five healthy caribou appeared on the ice and they did not run away. I thought I would not be able to catch them because there were no shadows. The land was flat without even a rock for cover. However, I was able to kill them with little effort. I was so grateful, that I shook their hooves as a sign of gratitude because they gave themselves up to my hunger. I melted the snow with my mouth and gave them each a drink. I was careful in removing the sinews so as to ease their spirits’ pain. This is the traditional way to show thanks. Because of what those caribou did, I always hunted in this way. I respected the animals.

— Nasby, 2002

He was a founding member of the Baker Lake print shop and appeared multiple times in the Inuit Art Quarterly.